Frank Byrd

FRANK BYRD attended King Edward VI School between 1891 and 1895, when the Rev. Robert Stuart de Courcy Laffan was Headmaster. Where he lived in the Shipston Road has changed little. The set of Victorian terraced houses is neat and attractive, and each morning he walked to School across the medieval Clopton Bridge over the River Avon, with the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre on the left and, in the distance, the spire of Holy Trinity Church. Sometime after leaving KES, he became a sidesman there as well as working with the children in the Sunday School. During those early years of the 20th century, he enjoyed a settled life as a clerk for Richard Martin Bird and Company, wine merchants of 32-33 Bridge Street. (The building remained a wine and spirits merchants, not Bird’s however, until the late 1990s).

Stratford-upon-Avon in July 1916 may have continued in its comfortable routine, but the War was always present. Whether in conversation, or the missing familiar faces, patriotic displays in shop windows, more flags flying, or the increasing number of ladies in black. The pages of the Stratford-upon-Avon Herald carried advertisements encouraging support for ‘our boys at the front’ and providing officers with bespoke uniforms. There was a larger, but ever more enthusiastic ‘War Notes’ column, that dutifully, and blithely, followed the official and the positive line: ‘Such a thrill ran through the country on Saturday July 1 when the first news of the offensive became known. There were extraordinary scenes in the principal thoroughfares when the newspapers began to announce the welcome tidings that a move of some sort had began. Newsvendors could hardly cope with the rush, and the story of the offensive went from mouth to mouth.’ Issues of the Stratford-upon-Avon Herald later in July and into August began to publish more grim news and ever longer columns announcing the death of Stratfordians at the front.

Frank Byrd had enlisted at the recruiting station in Sheep Street on March 27 1916 aged 37, and was transferred to France and to the 14th (Service) Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment almost immediately.

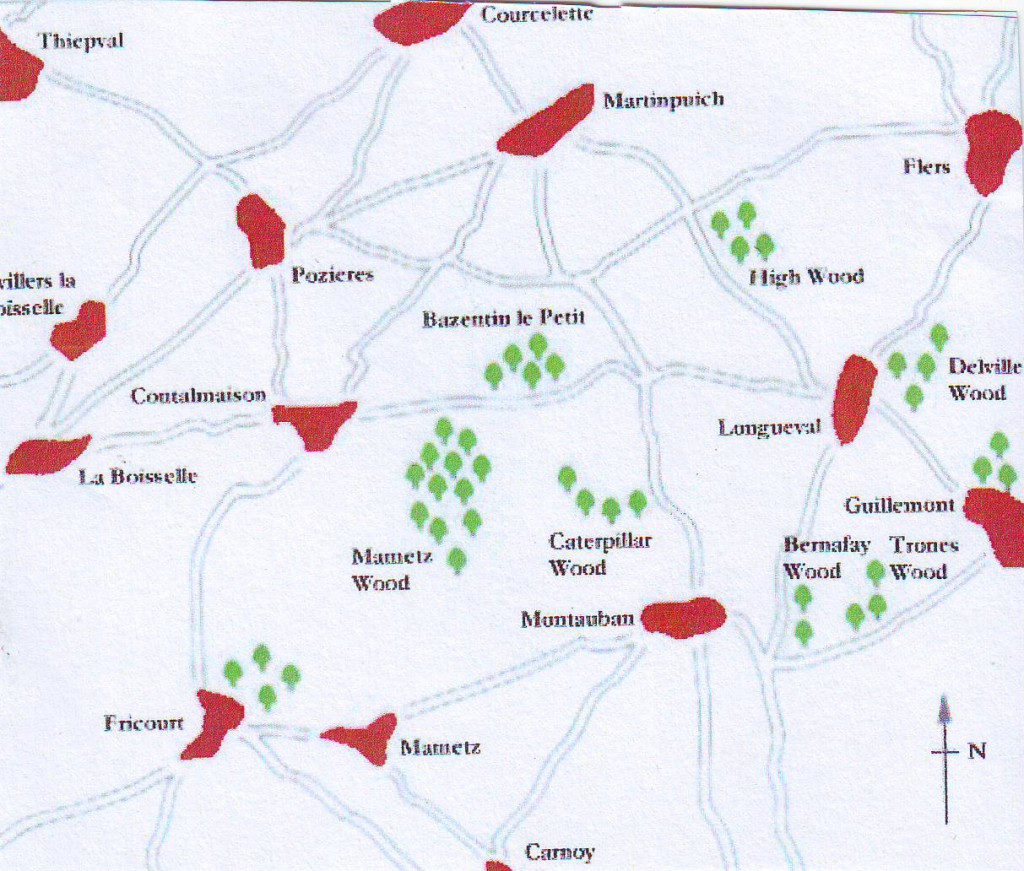

The 14th (Service) Battalion (1st Birmingham Battalion) –known as The Birmingham Pals – had been raised with accompanying civic fervour and pride, by the Lord Mayor and a local committee in September 1914. It moved on October 5 to Sutton Coldfield, and with three Pals Battalions it was transferred on June 25 1915 to join 95 Brigade, 32 Division in the riverside meadows of Wensley Dale in the Yorkshire Dales. On August 5 they moved to Codford on Salisbury Plain, and on November 21 sailed for France and landed at Boulogne. On December 28 1915, 95 Brigade, containing the men of 14 Battalion, transferred to 13 Brigade 5 Division. The men had much to learn and were at once launched on a programme of intensive training. Although they possessed both physical and intellectual attributes, most had been in the army for only about eighteen weeks when they were thrown into the Battle of the Somme. On July 19, Byrd was with 14 Battalion in support on the Longueval to Bazentin line, with the Germans concealed in High Wood. This was more than a geographical feature, but a much fought-over military strongpoint before and after July 1916. 14 Battalion received orders to attack at 10:00pm on July 22, in two waves with artillery support.

Map of the area around Mametz Wood

It appeared to be making good progress until it crossed a ridge when it was spotted in the light of German flares and were at once completely overwhelmed by savage machine gun fire. The artillery support, incorrectly ranged, had failed the battalion with devastating results. Six officers and 173 men were killed, with 195 men missing.

Withdrawn for consolidation and relief, the Battalion entered bivouacs near Pommier and Mametz on July 24, and were joined by a further draft of new men from England for further training. The men had not long to wait to apply what little they had learned, as they moved into attack positions to the west of Delville Wood late on July 29. This was the line along the lower segment of Black Road to the junction of Pont Street and Duke Street and eastwards to the junction with Piccadilly. Usually a hazardous manoeuvre, they succeeded without casualties.

Writing in the War Diary of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, the CO ‘was of the opinion that companies assembling for the attack would be in full view of a probable German observation post situated on the high ground north of Longueval.’ By 2:00am the following morning they were in position and sent out patrols to reconnoitre the German line. Running eastwards from the trenches now occupied by 14 Royal Warwickshire Regiment was a partly dug trench the aim of which was to connect a series of strong-points that were forward of the British line. Orders were issued for the men of C and D Companies to ‘dig themselves in as rapidly as possible, and improve by all means in their power this line of trench.’ Therefore, prior to the attack, their jumping off point was now 150 yards nearer to the German line. Following a preliminary bombardment, wit the main bombardment an hour later, C and D Companies left their trenches. The story of the attack was told by one who was in the front line and published in the Stratford- upon-Avon Herald: ‘We breakfasted early in the assembly trenches – every officer, NCO, and man only too eager for the signal to cross ‘No Man’s Land’. We were all in the highest spirits to be over the top. In fact, it was a case of Paradise Regained.’ Under the cover of the corn, they advanced until they reached striking distance of the German lines. They were quickly repulsed by intensive enemy fire from the strong defensive position, and those who could began to seek cover in shell holes approximately forty to fifty yards from the German trenches. The attack had ground to a halt. Although an army communiqué read that ‘The behaviour of all ranks was beyond praise,’ there was criticism that ‘the artillery preparation was too short. Throughout the bombardment the heavies were dropping very short, and at times shells landed behind and into our own front line trench. I am of the opinion that under cover of the corn fields, a successful infantry attack could be launched at the German trenches without Artillery preparation, which of course informs the enemy of our intention, and gives him time to prepare manning his trenches.’

14th Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment had been in the thick of fierce fighting for ten days. The cost had been heavy and at roll call the following morning, Frank Byrd was amongst the missing. For a time it was believed possible to hope that he had become a prisoner of war, but all hopes faded and it was accepted that he had been killed in action on July 30, a little over four months since he had enlisted.

The name of Frank Byrd appears on the Thiepval Memorial for the Missing on the Somme, on the Stratford-upon-Avon War Memorial, the Memorial Screen and Reredos in Holy Trinity Church, and in the Memorial Library at King Edward VI School.