Herbert Howard Jennings

On Saturday May 12 1923, the War Memorial Library was formally opened. In the south-west corner of the School quadrangle, it had been the wish of the Headmaster, the Rev. Cecil Knight, to commemorate those boys who had been lost in the War and have a lasting memorial to them, and also ensure that they would never be forgotten. The building, described as a ‘simple, beautiful example of British design’ was composed of Warwickshire oak timber. The windows were filled in with leaded lights, and some of the glass came from an old screen in Holy Trinity Church. The library bookcases, the large oak table and the bronze memorial tablet were presented by the historian Sir George Trevelyan.

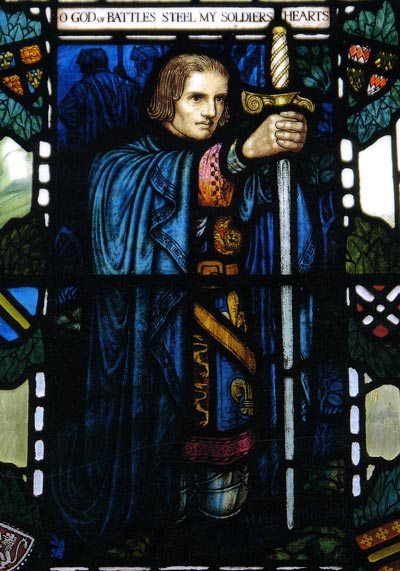

The north window contained stained glass panels showing Henry V praying the night before the Battle of Agincourt: Upon the king! (Act IV Scene I) It was presented by Mr. and Mrs. Howard Jennings in memory of their two sons, Second Lieutenant Henry Jennings of the 3rd Battalion, The Worcestershire Regiment (Chapter 7) who was killed in April 1916 and Lance-Corporal Herbert Jennings of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders who was killed in September 1918. The parents chose Henry V, feeling that ‘the illustrious poet who was educated here had, in his matchless language, depicted that spirit of sacrifice and love of country which are so essential today.’

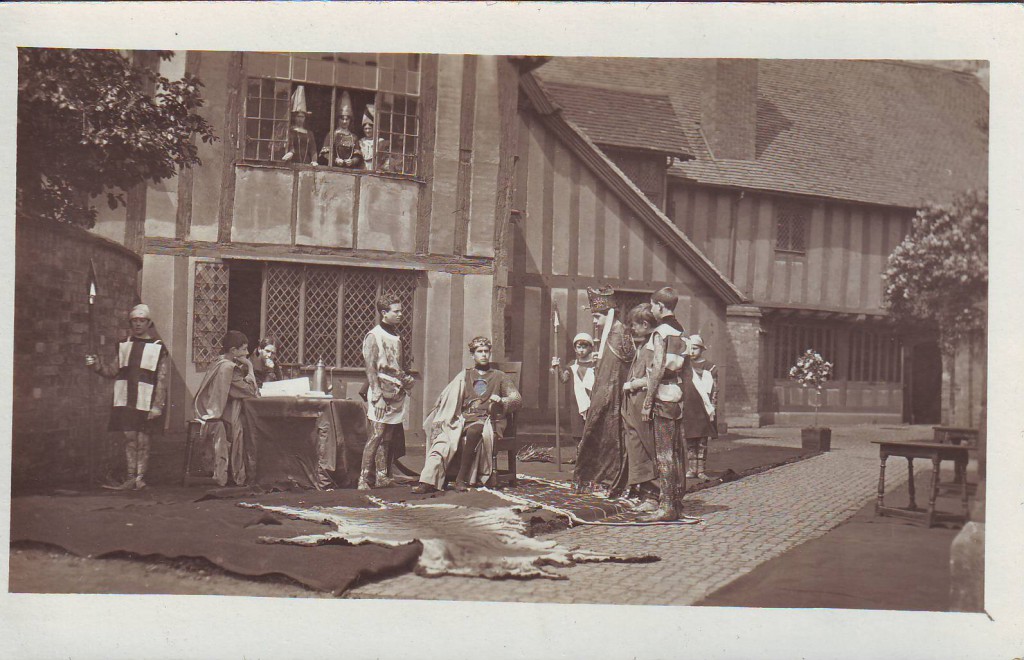

HERBERT HOWARD JENNINGS was the youngest son. He lived at Riverside in Tiddington just outside Stratford-upon-Avon where his father was an insurance manager, and following his early years at Stratford Preparatory School he attended King Edward VI School between 1911 and 1915. Whilst his brother Henry flourished on the sports field, being a member of both the 1st XV and 1st XI between 1911 and 1913 – earning colours for both – and excelling in athletics (he was Victor Ludorum in 1913), Herbert’s years at School were less energetic, but he did achieve notice, along with his friend Victor Hyatt, in the special 1913 production of Henry V performed as part of the annual Shakespeare festival in the Memorial Theatre by the Avon. Henry played Ancient Pistol, and Herbert’s speaking of the Earl of Salisbury…

‘God’s arm strike with us! ‘tis a fearful odds.

God be wi’ you princes all; I’ll to my charge:

If we no more meet till we meet in heaven;

Then, joyfully, my noble Lord of Bedford,

My dear Lord Gloucester, and my good Lord Exeter,

And my kind kinsman, warriors all, adieu!’

(Act IV Scene III)

…received favourable comment in The Morning Post.

It is unclear when Herbert Jennings arrived in France, having enlisted at Hounslow Barracks in the Lovat Scouts. Formed by Simon Fraser, 16th Lord Lovat and 22nd chief of the Clan Fraser, they were sharpshooters known for their stalking. Transferred to the 14th County of London Battalion (London Scottish), it was finally as a Lance Corporal in 1st Battalion The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders that Herbert arrived in France at the beginning of 1918.

In the field near Noyan, it was a relatively quiet time with no major German attack and the main hazard from the occasional sniper and artillery bombardment. In the first phase of the massive offensive of March 1918, the German left flank struck not far from the north of the Cameron Highlanders, but they were not in its path, and following a period of great confusion and defeat for the British army, by mid-April Herbert’s battalion had moved to Verquin near Bethune. Here, the second phase of the German offensive – Operation Georgette – had swept through Armentieres.

On April 18 the battalion was in the support trenches behind the Black Watch (Royal Highlanders), when the Germans were observed massing in front of their positions, and then advancing with all the purpose and tactical skill that had already gained them so much ground along most of the front. It seemed that they would sweep aside all opposition, and the Battalion Headquarters hastily burned all maps and documents before it became clear that the Black Watch would be able to halt the Germans.

Even in support, the Battalion had thirty-seven men killed in the Battle of Bethune. Although the German offensive continued until mid-July, it had outreached its strength and it had lost many of its elite units that had spearheaded the attacks. The French launched a counter offensive on July 17 in the south – the Aisne-Marne Offensive – and the British followed in the centre on August 8 and on September 27 and 28 in the north at Cambrai and St. Quentin.

The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders missed participation in the intensive action until September. On September 1 it moved forward from its billets in the caves near Arras, and late in the evening moved to its assembly point in readiness to act as reserve for a Canadian attack at Drocourt, ten miles east of Lens. As the Canadians advanced, the Camerons came under an artillery barrage, and advancing up a ridge it discovered that the Canadians were already in possession, so withdrew.

On September 3, once more in support and trying to move forward, it came under fire. It was a pattern that was to last for a number of days, until it was given a clearer role on September 18, ‘one of the bloodiest days of the whole war,’ wrote K.W. Mitchinson, in what became the Battle of Epehy that was directed against the forward posts of the Hindenburg Line. It formed up at 4:50am and advanced, with a creeping artillery barrage, over 1,300 yards on the German forward outposts.

Named by the British for the German commander-in-chief, Paul von Hindenburg – the Germans referred to it as the Siegfried Line – the Hindenburg Line was a semi-permanent line of defences that Hindenburg had ordered to be created several miles behind the German front lines in late 1916. It was considered by both sides to be impregnable.

After some delay, the Battalion captured the trenches and many prisoners, and was able to consolidate its position although still subjected to heavy machine gun fire. It progressed to a sunken road but here found that its right flank was exposed. Able to set up defences, it remained in a precarious situation that the Germans attempted to exploit. By 2:45pm, it was well established in good positions and once again pushed forward in order to capitalise on the emerging German weaknesses.

Two further determined attacks were made the following day when two platoons attempted to press forward, and it was during the second that Herbert Jennings was killed. It was just seven and a half weeks before the war ended. He was buried in the Bellicourt British Cemetery at Aisne, just north of St. Quentin.

Bellicourt British Cemetery, north of St Quentin

In reporting his death, the Stratford-upon-Avon Herald, on October 11, wrote ‘Sincere sympathy will be extended to Mr. and Mrs. Howard Jennings in the irreparable loss they have sustained on the death of their younger and only surviving son. So recently had he been seen in our streets in his picturesque Scottish attire which well became his manly and erect bearing that news of his demise last weekend came as a profound shock to all who knew him. His bright young life has been cut short at the early age of 18. To the bereaved parents, what words of sympathy can correspond with the depth of their grief. They had only two sons and the great reaper has laid claim to both on the blood soaked fields of France.’

In addition to the Memorial Library, Herbert Jennings is commemorated on the Stratford-upon-Avon War Memorial in the Garden of Remembrance, the Alveston War Memorial, and on the Memorial Screen and Reredos in Holy Trinity Church.