James Alwyne Wilkes

For many centuries, the beautiful and historic Guild Chapel in Stratford- upon-Avon embraced the life of King Edward VI School. Each morning, the boys filed in through the north porch entrance in Chapel Lane for prayers. Following the suppression of the Guild of the Holy Cross, and the whitewashing of the many medieval wall frescoes, the Chapel was granted by King Edward VI to the Mayor and Corporation of Stratford rather than an ecclesiastical authority. The Headmasters of the School had always been clergymen – this was to change in 1945 – and it was during the time of the Rev. Cornwell Robertson that JAMES ALWYNE WILKES was confirmed, at the age of 16, in the Chapel on May 271907 by the Right Reverend Huyshe Wolcott Yeatman-Biggs MA. DD, the Bishop of Worcester. James joined the School in September 1905 and he was a contemporary of several of those boys who were to fight and die in France and Flanders. His elder brother John was at the School between 1900 and 1906 and captained the 1st XI in 1904 and 1905, and was a member of the 1st XV between 1903 and 1906. A younger brother, Norman, attended between 1906 and 1907. James was also a member of the 1st XV when Cyril Hoskins was Captain in 1907. They lived with their father and mother, John Sebastian and Julia Gertrude, at Granby Farm near Tredington, just north of Shipston-on-Stour.

On leaving KES, James joined his parents to work on the farm, and just after harvest time he enlisted in the 1/1 Warwickshire Yeomanry on September 1 1914 for one year’s service at home as a trooper, but six weeks later signed an agreement to serve abroad. Based at St. John’s in Warwick, the 1/1st Warwickshire Yeomanry was embodied with the 1 South Midland Brigade, and on August 14 moved to Bury St. Edmunds where on September 4 it was brigaded with the 1/1st Worcestershire Yeomanry (Queen’s Own Worcestershire Hussars) and the 1/1st Gloucestershire Yeomanry (Royal Gloucestershire Hussars) to form 1st South Midland Brigade.

The Brigade joined 2 Mounted Division at Newbury, where it camped on the Racecourse and where it was inspected by King George V and the Division Commander before moving on November 16 to Sheringham in Norfolk for further training and preparation for action. It was becoming quite clear to most people that in the stalemate of trench warfare on the Western Front cavalry would find only a limited role, although it was to be kept in readiness behind the lines throughout the war. At first, Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, was reluctant to commit yeomanry regiments to the Dardenelles, but at the beginning of 1915, nine regiments were sent to Egypt and seven were to serve dismounted in the Gallipoli campaign.

The Ottoman Empire entered the war on the German side. A.J.P. Taylor considered that it was difficult to think of any rational motive for this act. ‘The Turks could not possibly gain from the war even if Germany won; indeed the only remote chance of survival of their ramshackle Empire was that they should keep out altogether. But they had been alternately patronized or bullied by Russia and Great Britain for a century past; now the temptation to strike against both at once was irresistible.’

In the autumn of 1914, the Russians had been hard pressed and appealed to Britain for a diversionary campaign in the Eastern Mediterranean to distract the Turks. Kitchener and Sir John Fisher, the First Sea Lord, urged an attack on the Dardenelles against Germany’s flank. The British Government ‘jumped at this wonderful solution.’ But the ‘side show’ proved a disaster, and was ‘a terrible example of an ingenious strategical idea carried through after inadequate preparation and with inadequate drive.’

On April 11, the regiment sailed from Avonmouth in the transport ‘Wayfarer’ with 763 horses on board to join the force being concentrated in Egypt for landing at Gallipoli. Sixty miles north-west of the Scilly Islands the ship was torpedoed and six of her holds were flooded. An hour later a small trading steamer the ‘SS Framfield’ came to the rescue and the men were transferred on board. ‘Wayfarer’ did not sink and some officers and men – including James Wilkes – volunteered to re-board her. With six holds flooded out of nine, and working for forty-eight hours to their waists in water, the men were able to save 760 of the 763 horses. Taken in tow by the ‘SS Framfield’, and with the horses up to their knees in water, ‘Wayfarer’ arrived safely in Queenstown Harbour. The whole party were mentioned in dispatches, and those ‘who gallantly undertook this arduous task’ were later awarded the Meritorious Service Medal. Following a short delay they arrived in Alexandria on the ‘Saturnia’ on April 24. The general and colonel set off at once for Cairo to buy horses for the regiment and in three days returned with 357. Whether this was to replace or supplement the horses that left Avonmouth is not known.

Although the first landings by British, Australian and French troops were made at Gallipoli on April 25, the 1/1 Warwickshire Yeomanry, with James Wilkes, was not to see action until August 1915.

In May and on into July, the Yeomanry was encamped at Chatby, where further men and horses arrived from England. Training began that was mainly tactical exercises without horses, and an inspection on the main Alexandria Road by General Shenton. The last of those men who had been torpedoed on the ‘Wayfarer’ arrived in mid-July. The War Diary records that some time was spent looking at the harbour defences, and three officers disappeared ‘on secret reconnaissance.’ At the end of the month, the General went to Cairo and returned with orders to make all arrangements for a move overseas.

Orders were duly issued on August 1, but two days later the move was cancelled but the regiment continued drawing equipment. Following a new order on August 10 to move to the Dardenelles, final arrangements were completed with the selection of officers and men. James Wilkes was amongst them. Saddles were stored. Although comprised of trained cavalrymen, the Yeomanry were to be employed unmounted as infantry in the Gallipoli campaign. About one third of the regiment was left behind in reserve to look after the horses.

On August 14 1915 the force, having received inoculations against cholera, embarked on the Ascania, and three days later arrived at Mudros Harbour on the island of Lemnos. Transferring to the slower ‘Queen Elizabeth’ it landed in the Gallipoli peninsula at Suvla Bay.

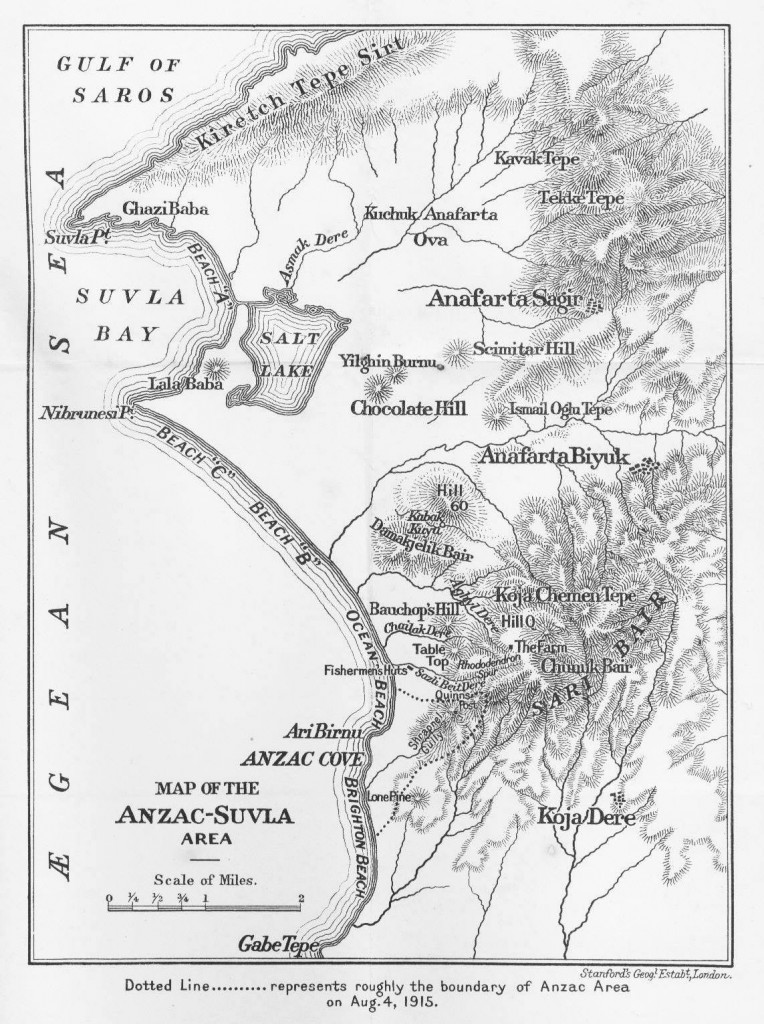

The 1/1 Warwickshire Yeomanry, dismounted yet part of the 2 Mounted Division, landed at Suvla Bay in the small hours of August 18, where it bivouacked on a hill and dug in under the eyes of the Turks, before what was to be the final phase of the British assault that had begun three days earlier. Subjected to very heavy fire it took its first casualties. The orders were for two British and Anzac infantry divisions to attack the Turkish positions on Chocolate Hill and Scimitar Hill that commanded Suvla Bay. 2nd Mounted Division was moved into a concentration area at Lala Baba, an advanced position out of sight of the Turks, with orders to be ready to exploit any success. On August 20 it moved out and marched to Lala Baba, and the following day continued on to support an intended advance on Chocolate Hill. The British artillery preparation was woefully inadequate because of a lack of ammunition, and the attacking forces suffered horrendous casualties. By 5:00pm it had failed and 2nd Mounted Division was called forward from its support position. Crossing the open ground of the dried-up salt lake, it was subjected to intense shrapnel fire. One hundred and seventy men of the Warwickshire Yeomanry were killed or wounded. General Hamilton, the British commander, was deeply moved: ‘Such superb martial spectacles are rare in modern war.’ A naval observer was even more lyrical: ‘The spectacle of yeomen of England and their fox-hunting leaders, striding in extended order across the Salt Lake and the open plain, unshaken by the gruelling they were getting from the shrapnel – which caused many casualties – is a memory that will never fade.’ The event is also immortalised in a famous watercolour by Norman Wilkinson: Salt Lake and Chocolate Hill, one in a collection gathered into a book ‘The Dardenelles’ and published in 1915.

As the troops reached fields beyond the Salt Lake, the order was given to ‘speed up to the double,’ but casualties continued to mount until they arrived at the foot of Chocolate Hill. From here the Brigade launched an attack on Scimitar Hill at about 6:00pm but was swept off by ferocious Turkish fire. Managing to establish a line lower down the hill, it continued fighting until 1:30 the following morning, but was mercifully evacuated in the small hours and withdrew to Chocolate Hill. For the rest of August and into September it was pinned down in its trenches and dug- outs under enemy shelling of varying intensity.

By the beginning of September, 757 men remained of the 1038 who had left Alexandria two weeks earlier. Sickness was rife in the trenches, and its effects had been clear in the attack on August 15. More than twenty-two thousand sick and wounded men had been transported by sea to Egypt and Malta, where the hospitals were officially declared to be full.

By the end of September 1915, the strength of the 1/1 Warwickshire Yeomanry had fallen further, to 526 officers and men. Although the month was spent under Turkish fire – both artillery and constant sniping – partly in reserve and in the front line trenches from Chocolate Hill to Lane End, it worked hard to improve its trenches, in spite of the shortage of sandbags. The main source of casualties during this time was ‘the prevailing illness.’ On September 18 and 27, the Turks carried out serious ‘straffs,’ and on September 29 120 men were carried off to hospital.

By October, sick parades had become even larger, shelling increased and the numbers of available fighting men decreased. On October 12, the Warwickshire, Gloucestershire and Worcestershire Yeomanries were amalgamated to form 1 (South Midland) Regiment of Yeomanry, but the line remained weakly held as sickness mounted and numbers continued to decline until it was finally relieved on October 20. Rumours had been circulating of a withdrawal for rest and recuperation, and at the beginning of November the Brigade was paraded and marched to Lala Baba. The Brigade embarked on the SS Ermine for the journey to Mudros. James, meanwhile, who had been confirmed in the rank of Lance Corporal on September 6, had left the Dardenelles earlier. Falling ill with slight pyrexia, he was admitted to the Government Hospital at Zagazig in Egypt. When his condition worsened to Paratyphoid B, he was transferred first to an emergency enteric camp at Port Said and then on December 8 by transport in the Hospital Ship Essequibo to England, where he was examined at 1st South General Hospital, Dudley Road in Birmingham on January 11. Granted home leave he returned to Tredington until February 21 1916.

Applying for a Commission on February 26 he was accepted as a Cadet Second Lieutenant on May 17. On probation in the 5th Battalion The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment at Pack Hall Camp in Oswestry, he was demobilised from the Yeomanry and ordered to report to No. 10 Officer Cadet Battalion at Gailes near Troon in Ayrshire. He successfully completed his training and was commissioned with the rank of Second Lieutenant on November 7 1916 (notification was published in ‘The London Gazette’ fourteen days later).

For some inexplicable reason he was ordered to the Machine Gun Corps. Created by Royal Warrant and followed by an Army Order in October 1915, the organisation of the Machine Gun Corps depended on the rate of the supply of Lewis Guns and this was completed before the Battle of the Somme. The base depot of the Corps was at Camiers, on the flat lands near Etaples in France. Being the targets of every enemy weapon, by 1917 the Corps had earned the nickname of ‘The Suicide Club.’

Prepared once again for front line service, Second Lieutenant James Wilkes embarked for France on March 30 1917 and joined his new unit in the field on April 6 at Queant, south-east of Arras. Heavily involved in the fighting of the summer and autumn during the saturating rain on the Ypres Salient, several of their guns were lost in the mud. It was active in the vicinity of Hill 70 in August, and at Cambrai as the offensive of the Third Battle of Ypres. Taylor wrote that the campaign had served its purpose. ‘What purpose? None. All the trivial gains were abandoned without a fight in order to shorten the line. Passchendaele was the last battle in the old style, though no one knew this at the time.’

Arras Memorial

In March 1918, the Germans had the situation for which they had long craved. They were free to fight a war on one front, for with the Treaty of Brest- Litovk, Russia had withdrawn from the war and Germany moved her armies to the Western Front with a new resolve to win decisive victory. American troops were arriving in France in growing numbers. ‘Germany’s associates, and particularly Austria-Hungary, were creaking at the joints’, wrote Taylor. This would be the last chance for knocking France and Great Britain out of the war.

The Germans were in high spirits. Following the largest bombardment ever seen on the Western Front, they launched their colossal offensive on March 21 1918 east of the old Somme battlefields, where the British-held positions stood on ground favourable for attacking infantry. By chance there was dense fog and they advanced quickly and overran the trenches held by James Wilkes and the Machine Gun Corps near Favreuil, north of Bapaume, almost unobserved.

The whole British line began to crumble, and an army trained to hold a trench had no experience of open warfare, and were driven back in bewilderment. Learning as they retreated, the Corps momentarily held at isolated redoubts at Poisieux Au Mont, Poullens and Mondecourt, and it was during one of these engagements that James Wilkes was wounded and died on Sunday March 26. He was 26.

He is commemorated on the Arras Memorial, Pas de Calais for the 35,000 British and Commonwealth servicemen who died in the area between Spring 1916 and August 7 1918 and have no known grave. He is also commemorated on the Tredington War Memorial and in the Memorial Library at King Edward VI School.