James Harbidge Yelf

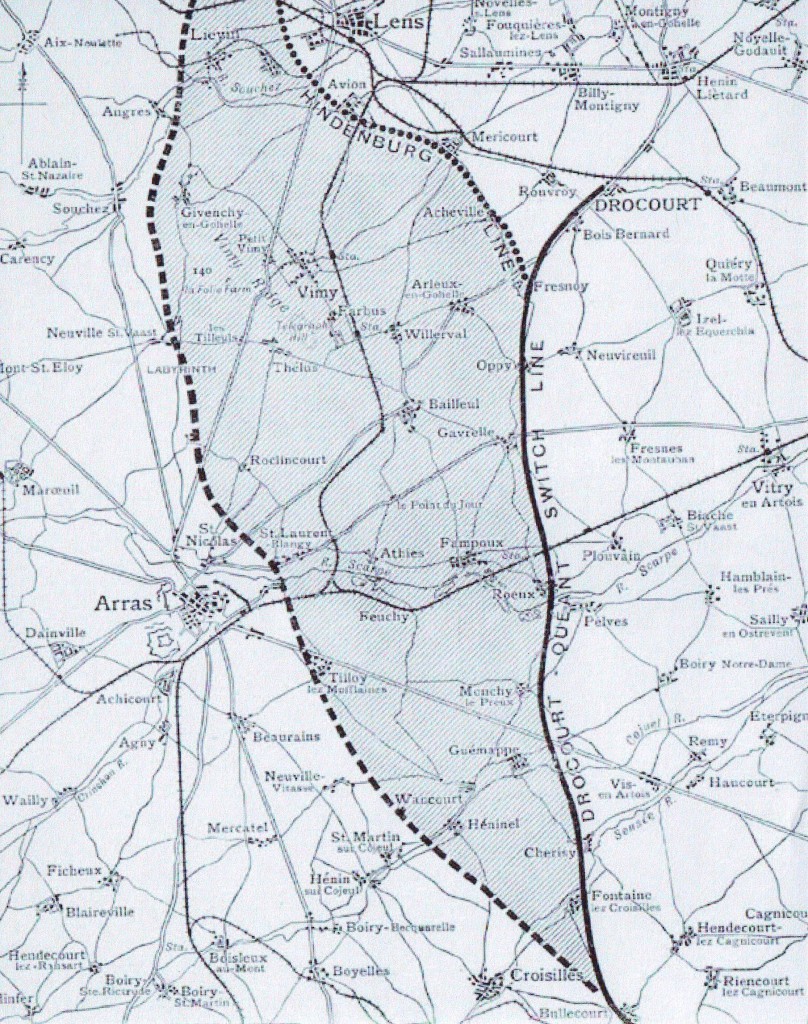

In October 1914, the German army occupied the chief coal-mining French town of Lens, and began to establish a series of strong fortifications, declaring them impregnable. Lens was to become the centre of a war fought from a warren of tunnels built at several levels beneath an area that was almost totally destroyed. It was to become the site of yet another tragic diversionary offensive in August 1917 in the region facing Vimy Ridge to the south of Lens.

In the summer of 1917, wrote A.J.P. Taylor, British strategy, ‘if such it can be called, reached its lowest level. Haig had come through three years of war still in high command and having learnt little from experience.’ He remained convinced that he could break the German lines and win the war by frontal assault. He always believed that it was in the Ypres Salient that he could break through and roll up the German line from the north, in spite of the fact that British soldiers were being ‘ground to death from both sides.’ The position appeared attractive on the map. He never inspected the front line. He disregarded the warnings of his own Intelligence Staff against the mud, and resolved blindly that this was the place where he could win the war. ‘Preparations were made on the usual elaborate scale. The Germans duly warned, prepared also. Their strength grew until it was almost equal to the British. Each side crammed nearly a million men into the Ypres salient.’ Divisions of British cavalry waited for the breakthrough that never came. ‘Rain fell heavily. The ground churned up by shellfire, turned to mud. Men, struggling to advance, sank to their waists. Guns disappeared in the mud. Haig sent in tanks. These also vanished in the mud.’

Into the heart of this area west of Vimy, arrived the 47 (West Ontario) Canadian Infantry attached to 10 Brigade 4 Canadian Division. In the 3rd Company was JAMES HARBIDGE YELF who had emigrated to Canada around 1903, settled in British Columbia, married Katherine Hester Cautley, and was a successful Master Mariner out of Vancouver. Born in Moreton-in-Marsh in the Cotswolds on the Fosse Way in February 1882, he was the youngest son of Dr. and Mrs. Leonard Keatley Yelf, and he attended King Edward VI School between 1893 and 1895, where the Headmaster, the Rev. Robert de Courcy Laffan remembered him as having ‘a bright boyish face, and I thank God for any little thing that I was able to do to help in building up that splendid spirit that he showed.’ Unlike several of his contemporaries – some who lived within walking distance of the School – James was not a boarder but each day made the journey of fourteen miles, morning and evening.

He served seven years in the Royal Naval Reserve before moving to Canada. Five feet eight inches tall and with the ruddy complexion of a sailor, he enlisted in the 143rd British Columbia Bantams in September 1916. Allocated to 143 Railway Construction Battalion, Overseas Battalion Canadian Expeditionary Force, he embarked at Halifax, Nova Scotia on February 17 1917, and crossed to England on SS Southland, arriving ten days later. On March 12 he transferred from 23 to 47 Battalion which was attached to 10 Brigade in 4 Canadian Division in the field, west of Vimy. He served in the same unit, the same division, and the same brigade – but not at the same time – as George Ball (Chapter 15).

Following days of training and some sport, he had his first direct contact with the war with working parties actively engaged in digging communication trenches whilst under sporadic German artillery fire. By June 16, James was in the line, where responding to signs of movements in and around the German trenches, a minor operation sent two Companies into a limited attack, against what turned out to be light opposition that successfully secured a German front line trench with some of the support trenches.

Both July and early August brought further driving torrential rain, and although Yelf was thankfully out of the line and changing positions within the Canadian sector, there were ever growing indications that another, larger-scale attack was imminent.

Following their victory at Vimy on April 12 1917, the Canadians continued their operations in the area of Arras in order to divert German attention from the French front and to conceal the major offensive planned in Flanders. Plans for the large scale frontal assault on Lens were changed to an attack on two hills north of the town. Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie, Commander-in-charge of all Canadian troops, felt that the losses in taking Lens would be unacceptable. He believed that taking Hill 70 would not be easy, and that casualties would be high, but would be considerably less than leaving the Hill under German control. It was a perfect defensive position, comprising a maze of deep Trenches, dugouts and deep mines. In front of the trenches was coiled barbed wire, up to five feet high, making a frontal assault difficult. Machine guns were deeply entrenched in the slopes inside reinforced concrete pill-boxes. He also appreciated that the Germans would attempt to retake the Hill, but that the Canadians would then have the advantage of the high ground, and therefore would inflict significant losses on the Germans.

Furthermore, occupation of the Hill, Currie called it ‘bite and hold’, would give the Canadians the opportunity of shelling the Germans and weaken their positions at Lens.

There would also be the added element of surprise. Leaving nothing to chance, the plan was rehearsed in the area behind the lines that was laid out to represent Hill 70. In addition, the whole area was to be subjected to intense bombardment, and by gas being heavier than air, would sink to the lowest area of the defending trenches and caverns.

The attack began on August 15 with the artillery providing a ‘rolling barrage’ and smoke screens. Yelf was with the 4th Division which was making a diversionary attack on Lens.

Success was achieved initially in the first twenty minutes as ten battalions took the high ground of Hill 70. Using a new tactic to demoralise the Germans, drums of burning oil were dropped into the deep trenches spreading smoke and flame over the Hill, whilst low flying aircraft identified pockets of resistance and signalled the co-ordinates to the artillery.

August 16 was very hot, and at 9:00am the Germans began to counter-attack with a barrage of high explosives, flame throwers and mustard gas. Because of the gas, the Canadians had to fight fully clothed and with gas masks, and because of the heat several died from both physical and emotional exhaustion. Wearing a gas mask made the men half blind, but removing it could cause a horrible death as the mustard gas blistered any exposed skin and seared the lungs. We can only imagine what those men endured.

The Germans counter-attacked with everything they had and subjected the Canadians to intense artillery shelling. Suffering from lack of rations and water, and with their ammunition desperately low, the Canadians attacked with bayonets in ferocious hand-to-hand fighting. Altogether the Germans counter-attacked twenty-one times suffering enormous casualties. The Canadians held their ground tenaciously by the skilful use of machine guns and the creation of a deliberate ‘killing ground.’

It is not an overstatement that the victory had not come easily with 5843 Canadian dead and wounded. Some companies sustained over 70% casualties. Lens was not taken and Hill 70 was secured. The Germans had been successfully stopped from using this ground as a staging area to attack the British position at Ypres. ‘Unfortunately,’ wrote John Stevens, ’the British attack that was being protected by this action was still doomed to become one of the worst experiences of the war as the mud-filled killing ground of Passchendaele would prove far more difficult than imagined.’

The Vimy Memorial

Sometime during the final German counter-attack James Yelf was killed and his body was never recovered. He is one of the thousands commemorated on the majestic Vimy Memorial that commemorates all fallen Canadian soldiers of the Great War, particularly the 60,000 who died in France of whom 11,000 have no known grave. James is also remembered on the Moreton-in-Marsh War Memorial, on the Memorial and Reredos in St. David’s Church in Moreton-in-Marsh, and in the Memorial Library at King Edward VI School. His wife Katherine moved to England to live near his parents, and bought Salteswell in Little Compton between Moreton-in-Marsh and Chipping Norton in Oxfordshire.