Henry Bernard Wilson

In the Minor Counties Championship match at St. Clare Ground, Penzance, in 1911, HENRY BERNARD WILSON played for Cornwall against the Kent Second XI. ‘This honour,’ reported The Stratfordian, ‘coupled with being first reserve for the same county’s football team, reflects great credit on his athletic prowess.’ The third son of the Reverend Herbert and Ada Wilson of Rowley Crescent, Harry Wilson had been an enthusiastic sportsman at King Edward VI School between 1901 and 1907. In the 100 yards for under 12, and as a member of the Gymnasium VIII ‘he was a young man of exceeding promise.’ He was a leading member of the games committee, was appointed a monitor, and was captain of cricket, gaining his colours, and judged ‘the best all-round cricketer in the XI.’ Also possessing a marked aptitude for rugby, he was appointed captain of the 1st XV in his final year at school. ‘He could always be relied upon never to let his side down, and yet was capable of bringing off a daring coup and changing defeat into victory.’

On leaving School, Harry joined the Eastern Telegraph Company. It had been formed to provide a telegraph cable connecting India with Europe. When war broke out in 1914, Wilson was in Aden where the cable from Bombay was linked on to Suez. As soon as he was able, he enlisted as a private in the Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) and served with it in the trenches in France for eighteen months from March 1915.

Wounded twice, he gained a commission on September 22 1916 in 15 (Service) Battalion (2nd Birmingham Battalion) The Royal Warwickshire Regiment – ‘The Birmingham Pals’ – that had been raised by the Lord Mayor in September 1914. Landing at Boulogne on November 21 1915 it joined 13 Brigade in 5 Division. After being in Budbrooke Barracks, two miles from Warwick (the site is now the village of Hampton Magna) Harry Wilson probably joined his new Battalion in late September 1916 when it was in the area of Guillemont, about eight miles east of Albert.

This was a difficult period for the army, primarily because of the very wet weather that swelled the dykes and ditches and made the ground and the trenches impassable in places. By November patrols were actively resumed, and on December 6 Harry Wilson led out a night reconnaissance patrol although they encountered no Germans. The following night he went out alone and returned with a curious notice that the Germans had planted near their trenches: ‘Bukarest is in our hands. Bavarians have taken it.’

The following night he went out again, this time with ten soldiers, and for two hours they checked on the condition of the dykes. One of the dykes, twelve feet wide and containing a foot of mud and water, was a difficult obstacle in which to move and they halted about fifty yards from the German front wire.

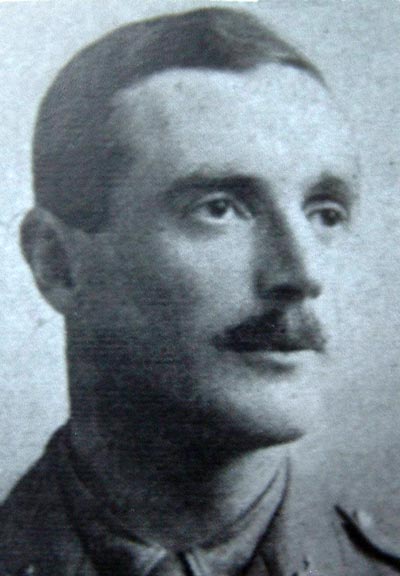

Henry Wilson, 1917

The remaining days of the month passed in routine, as did the first months of 1917, and it was not until April and the Battle of Vimy that Harry Wilson saw serious action as an officer. The 15 Royal Warwickshire Regiment was in support at Neuville St. Vaast as Canadian troops went into action on April 9. At 5:30am an intense concentration of British artillery fire fell on the German first line, moving forward one hundred yards every five minutes. Within two hours the first and second objectives had been reached and the Royal Warwickshire Regiment moved to its forward assembly area. Over broken ground the progress was difficult, but it was able to move forward and consolidate successfully. All its objectives had been reached plus the capture of many prisoners and materials. During the night as rations were brought up, the Battalion ‘stood to’ for an expected counter-attack that did not come. Orders to assist the Canadians at Vimy were changed, and as the Battalion withdrew from its camp at Grand Servin, a grateful Canadian band played. The Battalion losses were relatively light compared to those suffered by the Canadians.

The increased activity continued into May in the same area, as the Germans shelled the front line for a whole day and the constant threat of snipers and machine guns prevented runners from moving. In a series of small-scale attacks on successive days, the Royal Warwickshire Regiment lost six killed and eighteen wounded, then six officers and seven men killed, six offers wounded, 137 men wounded and fifty-six missing. Withdrawn for rest and training, it spent much of June reorganising and in support.

In mid-July, a German raid was driven off, and in late August Harry Wilson led out two small patrols of six men to investigate Devon Trench. On the first they came upon a German patrol that fled and on the second discovered fresh wiring.

In September the battalion moved to Flanders in order to join the build-up that would attempt to break through the German defences in that sector and into the northern plains, and at the same time relieve the pressure on the French armies that had suffered very heavily at Verdun. The Battalion was held in reserve and standing by during the Battle of Polygon Wood. The Wood had changed hands several times during the early years of the war and had been devastated by shell- fire, reducing it to a forest of tree stumps and saplings. Following a further period of training, it was equipped for action and inspected on October 20 by the Corps Commander, General Morland, before taking over the front line on October 24. The following day as it moved to its assembly areas, it lost five men killed and seventeen wounded.

On October 26 the Second Battle of Passchendaele began, and 15 Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment was to attack in waves on a one platoon front. To its left the ground was boggy and impassable, but at zero hour it advanced to a clearing and came under very heavy machine gun fire, causing many casualties including all the company officers. Supporting the 14 Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment, the Battalion helped to capture the chateau at Polderhoek and consolidation began.

The following morning at 8:00, the Germans were observed to be massing for a counter-attack, and fifteen minutes later the attack was easily repulsed by a combination of machine guns, rifle and Lewis gun fire. Two hours later the Germans massed and advanced again, and by 10:45am the British position had become critical as it saw that its right flank had been encircled. The condition for fighting was becoming indescribable, and many of the guns were clogged with mud and out of action. Continuing to take heavy casualties, the Battalion fought the way back to its starting line, but losses for the day included 31 men killed, seven officers and 113 men wounded, and forty-seven men missing.

Withdrawn for rest and further training through November, the Battalion was ordered to Italy on December 11. Harry arrived at about the same time as his contemporary at KES, Bertie Ellis, who was in 1/7 Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. The Austrian army had gained an important victory at Caporetto in October and had driven the Italians back to defensive positions along the River Piave. The British and French were forced to send eight divisions to support their ally. Following the long, twelve-day journey to Italy, the Royal Warwickshire Regiment was in the front line on the south bank of the Piave and in reserve at Arcade. Already the pressure had relaxed and it was not needed. The Austrians were unable to continue any aggressive activity until June, by which time 5 Division had returned to France.

On March 21 1918 the Germans launched a major offensive on the Western Front that broke through the British lines and drove them back, in places to within forty-five miles of Paris. For a period, the war became one of movement, with the British and French desperately seeking to establish new defensive lines from which to fight their way forward. Haig issued his famous Special Order of the Day on April 11. But by April 6 the German attack had outrun its strength and had come to a standstill. By April 12, the Royal Warwickshire Regiment had been rushed into bivouacs near the Nieppe canal.

Harry was with the Royal Warwickshire Regiment when it took part in the costly action known collectively as the Battle of the Lys. On the first day of the Battle of Hazebrouck on April 12, it was called forward from its bivouacs at 12:05pm near the Nieppe canal with orders to dig a line and form an advanced guard for a Division attack. After two companies had prepared the way, the Battalion advanced at 3:30pm to take up a forward position. At 5:15pm it made contact with the Germans who were holding a house and brickfields at Le Corbie. The advance was checked by ‘considerable machine gun and rifle fire.’

In response to orders to capture these positions, the Battalion launched an attack from the north. Clearing and holding the brickfields, they established posts and a line, but were prevented from establishing contact with the division on the right as the enemy was massing threateningly across the canal. At 8:00pm an attack supported by heavy enfilade fire was repulsed, but the Germans were able to advance along the canal bank. As the Royal Warwickshire companies reorganised and consolidated, fresh orders were received to adjust the line as the brickfields were fired by enemy artillery. The battle continued into the night, and as ordered, the line was re-established and the Battalion HQ was moved.

By morning the front was much quieter, but after midday German artillery became very heavy and small parties of its soldiers were observed assembling at a crossroads. For the next twenty-four hours any relief was impossible, as the enemy was again seen massing out of rifle range and the Battalion’s neighbours were under threat. Two frontal attacks were beaten off, but they were succeeded by heavy shelling for eight hours.

There was more sustained German artillery shelling from 6:00am the following day, followed by a heavy attack at 12:30pm. Although relief came and the attack was beaten off, in the two days of fighting the Battalion had lost four officers killed and five wounded, twenty-three other ranks killed, and 176 wounded.

For some time, Harry Wilson had wished to fly. As the Army General Staff began to appreciate the potential for aircraft as an effective method of reconnaissance the Royal Flying Corps was formed on April 13 1912. By the beginning of the war Britain had 113 aircraft in military service, and their main responsibilities were to support the army through artillery cooperation and photographic reconnaissance. Soon the RFC pilots were in aerial combat with an enemy flying superior aircraft, and British casualties were high until the arrival of improved fighter planes, such as the Sopwith Camel and the Airco DH-2,established British superiority over the Germans. On April 1 1918, by the amalgamation of the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Flying Corps, the Royal Air Force was formed as an independent armed service, and Harry Wilson joined as a pilot at the first opportunity in May 1918, ‘showing much proficiency in the air.’

On August 14, he flew over Stratford-upon-Avon and dropped a message to his mother. The following day in Wiltshire he was testing the new Sopwith Snipe. Basically a larger version of the Camel, it was considered easier to fly and gave better visibility from the cockpit. For reasons that are unclear – ‘a mishap occurred’ – the Snipe crashed and Harry was killed. To have survived so much fighting and then to die in such an accident was tragic.

The Stratford-upon-Avon Herald reported on August 23 1918, that ‘en route from the station to the cemetery there were many signs of sympathy with the family.’ His mother, brother and sister were at the cemetery – his father had died the previous year. ‘The coffin which bore the inscription ‘Lieutenant H.B. Wilson 36 T.D.S. died August 15 1918 aged 27 years,’ was covered with the Union flag and four of his brother officers, Lieutenant Davis (The Royal Warwickshire Regiment), Lieutenant Black (The Highland Light Infantry), Lieutenant Stackhouse (Royal Air Force) and Lieutenant Patterson (The King’s (Liverpool Regiment) acted as bearers. The Lieutenant was buried with full military honours, a firing party being in attendance from Budbrooke.’ The service was conducted by the vicar of Holy Trinity Church, the Rev. Canon Melville, whose parish magazine for September 1918 reported Harry’s death and that ‘his body rests with his father’s “till that day”.’

Harry Wilson is commemorated on the Stratford-upon-Avon War Memorial, the Stratford-upon-Avon Cemetery War Memorial – where he lies amongst the tall cedar trees – the Memorial Screen and Reredos in Holy Trinity Church, and in the Memorial Library at King Edward VI School.