Alan Moray Brown MC

The story of the 160,000 strong trained British Indian army on the Western Front started on August 6 1914 when the War Council asked the Indian government to send two infantry divisions and a cavalry brigade to Egypt. On August 27 the British government decided to send the Indian divisions to France in order to reinforce the British Expeditionary Force that had recently been forced to withdraw after Mons.

Its new destination was Marseilles which must have been a wonderful sight in those days as it was also the port where most of the French colonial troops arrived. The British officers compared the behaviour of their troops with those of the Algerians, Moroccans, Tunisians and Senegalese. During the fourteen months that the British Indian Corps stayed in Europe (before its transfer to Mesopotamia), Marseilles was the Indian base port, and the troops were always enthusiastically received by the French population.

The village of Queen Camel in Somerset remains the similar compact market town near the small river Yeo that ALAN MORAY BROWN would have known as a boy one hundred years ago. The son of James Moray Brown of the 79th Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders and Anna Maria Moray Brown who was related through her father to the family of William Pitt the older and younger, they lived west of the village in Wales House. Alan boarded at King Edward VI School in the handsome nineteenth century School House in Chapel Lane between 1892 and 1899, and under the care of two progressive Headmasters – Robert de Courcy Laffan and Edward Houghton.

He positively flourished during his years at School, where he became Head of School House, a Monitor, captain of Cricket and of Rugby – winning colours in 1898. The Stratfordian reported that ‘he proved himself to be a most efficient and hard working Captain, always setting an admirable example to the team by the keenness and interest he displays. He shows to great advantage playing as he does behind a tight scrimmage, his saving being both plucky and brilliant. He is a safe tackler and a good kick.’ He was on the Games Committee, in the Gymnasium VIII, and excelled in the 1899 steeplechase that wound around Clifford Chambers and beyond to Atherston-on-Stour.

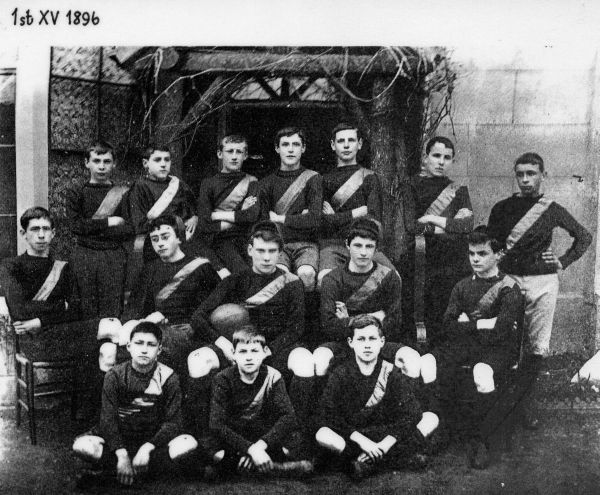

The 1st XV, 1896, Alan Moray Brown is first left on the back row

He was awarded the Modern Language Composition prize in 1897, which two years later he won again as well as the English History Prize, and gained the Shakespeare Scholarship. Leaving School in 1899 he passed directly to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. Placed 9th in the final examination in 1900, he obtained a commission in the Indian Army Staff Corps. He was the third generation of his family to serve in the Indian Army. Arriving in India as a Lieutenant, he was attached to the Bedfordshire Regiment at Mooltan, on the east bank of the Cheneb River in the Punjab. He kept in touch with KES with news for The Stratfordian that he had published an article in the ‘Asian’ magazine on Partridge Shooting, and by sending a contribution of one pound for the new Fives Court.

Alan reached the rank of Captain on July 28 1909, and served in China before his appointment to the Staff of 4 Indian (Quetta) Division. Following a year attached to the Bedfordshire Regiment, he joined the 47 Sikhs, Jullundur Brigade, 3 (Lahore) Division.

The Division was able to respond quickly to the order of mobilisation that came on August 8 1914, and ten days later it moved by train to Karachi, where on August 29 seven British officers and eighteen Indian officers, 809 NCOs and men and 73 followers embarked on the SS Akbar. After arriving at Suez they travelled on by train to Cairo and Alexandria, where they re-embarked on the SS Akbar to join a convoy for Marsailles that arrived on September 26. Here they were inspected by General Serviere in the Borely, a large park quite like the Parc de Vincennes in Paris. Continuing by train to Orleans they spent the following two weeks in final training exercises.

The 47th Sikhs was an ethnic homogeneous battalion. A trooper was a ‘sowar’, and a very particular relationship existed between the British officers, the Indian NCOs and the rank and file, best described as paternalistic. The British officers often not only spoke the language well – Alan Moray Brown had been one of five out of sixteen candidates who had passed the first language test for British officers in India in 1901 – but there was a general mutual respect from the officers towards the Indians and vice-versa. When a large number of British officers died in the first battles, many Indian soldiers felt dazed and alone without those officers who understood them and knew their culture and their habits. Indian companies of which the commanding officer was lost were brought under the command of British units – the brigades consisting of two British and three Indian battalions – where no one understood them. Feeding the Indian troops who represented every cast and creed was soon a major problem. Beef was not acceptable to many and since pork was absolutely taboo, all France as far afield as the island of Corsica was scoured for goats, as old and as tough as possible to supply the Indians’ needs. Officers, like Moray-Brown who had served with the Indian Army in peacetime understood this, but as casualties mounted and they were replaced by others with no experience of Indian troops, difficulties and misunderstandings increased.

On October 17, Captain Moray Brown and four NCOs went ahead to arrange billeting behind their newly allocated sector of responsibility. The 47th Sikhs were billeted in a large monastery near Saint-Omer on October 14 1914 and were well received by the monks. However, the curious troops continually scrutinised the statues of the twelve apostles in the main corridor of the abbey, finally accepting the explanation of the British officers that these were images of Christian gurus.

Map of the Neuve-Chapelle area, 1915

At this early stage in the war there was a great deal of confusion and a clear dividing line of trenches had not been established. On October 23 the Battalion moved into a support position on the right flank of the French cavalry with the British 19th Brigade, with orders to engage the enemy only if needed for a counter- attack. The 47th Sikhs were deployed in the vicinity of Neuve-Chapelle. It soon became the Indian Sector. The men endured the constant icy chill of the northern marshes and dreadfully bad trenches. The British Indian troops, vaselined and oiled to the waist, were thrown piecemeal into the heaviest fighting. The Indian charge captured part of Neuve Chapelle village but had to retire before a strong German counter-attack with strong machine-gun support. Captain Moray Brown rallied his men under heavy artillery fire, but returned with only sixty-eight, and they were at once ordered by the GOC 9 Brigade to form a picquet at a crossroads before they could eventually return to Estaires. As a result of his actions, Alan Moray Brown was awarded the Military Cross.

The fighting came as a shock to soldiers more used to colonial warfare, and by early November the 47th Sikhs had only 385 men fit for duty. One soldier wrote home ‘this is not war; it is the ending of the world.’ The losses were so heavy that the Indian Corps had to be reorganised. On December 20 and 21 the Battalion was involved in the battle of Givenchy, first making an abortive attempt to support a French initiative and then a full-scale attack. The left wing of the attack was held up by machine gun fire and Moray-Brown was one of the many casualties. He was carried to hospital and the 47th Sikhs were taken out of the trenches and rested until early 1915.

Returning to the line on March 3, there were a few quiet days before the storm of the battle of Neuve Chapelle that began on March 10. Not involved on the first day, the 47th Sikhs could hear the British artillery bombardment and welcomed the news that the German front line had been taken. On the following day, as the snow swept down, they rose from their flooded trenches and cleared the village with hand-to-hand fighting in the streets and houses. For two days they were subjected to intense shrapnel fire and high explosives, during which Alan Moray Brown was mortally wounded. A.J.P.Taylor in ‘The First World War’ wrote: ‘The attack took the Germans by surprise. The British infantry broke the German line – for the only time in the war. Nothing of any significance followed. The British hesitated to enter the hole which they had made.’

They waited for reinforcements; but by the time these arrived, German reinforcements had arrived also, and the gap was closed. ‘Neuve Chapelle lasted a mere three days, not much by later standards, but it was a warning of what was to happen again and again: success at the beginning which led nowhere, and then attack going blindly on when they had already failed! To hesitant leadership at every level, was added poor communications and a cumbersome chain of command,’ wrote Alan Clark in ‘The Donkeys.’ Four officers and twenty-four men of the 47th Sikhs were killed, sixteen officers and 233 men were wounded, and seventy-two were missing.

Taylor wrote that the battle had another importance for English people. The C-in-C Sir John French, to conceal his failure, complained that he had been short of shells. The Government in turn blamed the munition workers ‘who were alleged to draw high wages and pass their days drinking in public houses.’ Legislation was introduced to restrict the hours when public houses were open, and in particular, ‘to impose an afternoon gap when drinkers had to be turned out.’ For the next ninety years, until new licensing laws came into force in 2005, ‘anyone who felt thirsty in England during the afternoon was still paying the price for the battle of Neuve Chapelle.’

The battle of Neuve- Chapelle ‘exemplifies the way in which the relation of attack to defence remained constant,’ wrote Alan Clark. The British view was expressed in a GHQ memorandum dated April 18 that concluded with the assertion that the ‘lessons’ of Neuve-Chapelle were that ‘…by means of careful preparation as regards details it appears that a section of the enemy’s line can be captured with comparatively little loss.’

Indian War Memorial, Neuve-Chapelle

There is a beautiful Indian War Memorial to the Missing to be found in the village, and at its dedication in 1927 Marshal Foch declared that ‘by their ardent spirit they delivered (Neuve Chapelle) from the grip of a determined enemy. They showed us the way, they made the first steps towards the final victory.’ A Sikh soldier wrote home: No one has any hope of survival, for back to Punjab will go only those who have lost a leg or an arm or an eye. The whole world has been brought to destruction.

Captain Alan Moray Brown died on March 12 1915 aged 34, and lies buried in the Guards Cemetery at Windy Corner, in the now peaceful village of Cuinchy, five miles east of Bethune. The cemetery was begun in January 1915, and it is likely that Alan’s grave was moved there from Neuve Chapelle after the Armistice.

The Indian soldiers fought with great bravery but had serious problems. The climate too was very harsh for them. Frostbite, influenza and pneumonia took their toll, and the Indians had their first encounters with mumps and measles that swept through their ranks. ‘But the cold,’ wrote Lyn Macdonald, ‘was worst, and the Indians could hardly remember the sensation of being warm, still less the fierce heat of the Indian plains burning under the sun they called ‘the Bengal blanket.’

To exacerbate their unhappiness, the troops fought for a cause they hardly understood. In January 1915, a Sikh soldier wrote: ‘This country is very pleasant, but it is very cold here. Nobody has any clue about the language. They call milk ‘doolee’ and water ‘doloo’!’ Lyn Macdonald wrote that ‘it was no unusual sight to see turbaned Indian troops hunched over tiny cooking fires, cocooned in a dozen or more khaki scarves and shawls plaited and knotted across khaki overcoats.’

Guards Cemetery, Windy Corner, Cuincy. (Marietta Crichton Stuart)