Alfred Bennett Smith

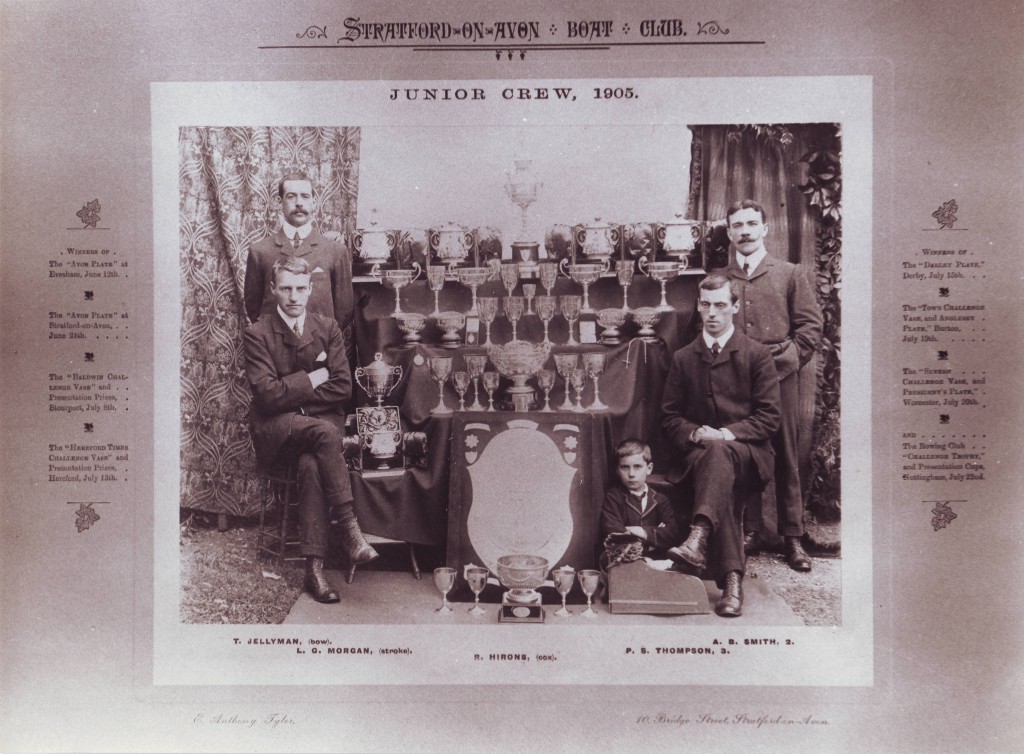

It was an all-Stratford final at the Evesham Regatta in 1905, where sixteen crews contested the Maiden Fours that was won by the crew of Tom Jellyman (bow), ‘Doc’ Smith, Pat Thompson and ‘Nonny’ Morgan. This four also won seven Junior events at the Stratford regatta, at Derby, Stourport, Hereford, Burton, Worcester and Nottingham. ‘It was,’ wrote a local oarsman, ‘the best junior combination that ever represented the Stratford Boat Club, and laid the foundation of the successive senior crews which, mainly through Doc’s coaching abilities and enthusiasm, brought successes to the Club, and gained for it high renown in provincial rowing circles. Some members of this junior crew went on to form a Senior IV that ‘covered itself with glory,’ winning six trophies, retaining the King’s, winning the Gold Vase, the Bedford Grand and the West of England. In 1909 the same crew again won six events, and retained the West of England, the King’s and the Bedford Grand. ‘It was characteristic of him that he declined a seat in the senior crews of 1906, 1908 and 1909 to which he was justly entitled, as he felt that, by acting as coach he could render greater service. Like a true sportsman he subordinated personal considerations to the interests of the Club, and how fully his action was justified was demonstrated by the success obtained by the crews during his captaincy.’

His sporting qualities and never-failing humour were recalled by a Club member some years later: ‘during the last time he took part in the annual races. It was a wet, chilly evening, and ‘Doc’ was standing on the raft in his scanty rowing attire, impatiently awaiting the crew who were sauntering down one by one, indifferent alike to time and climatic conditions. On being greeted with the remark, ‘Hello Doc, going to row?’ he sarcastically replied, ‘No! I am going to a fancy dress ball!’

William Collins (an Old Boy of King Edward VI School and a fine rower in many crews) wrote in his History of the Boat Club, that it remained open for pleasure boating during the war, and that the Members’ Book was kept with the addition, in red ink, against a name: ‘Died on the Field of Honour.’ ‘A description that could only be used in a less complicated, and more unquestioningly patriotic age than our own.’ In 1921 the Club War Memorial, a sundial on the lawn, was unveiled by the president, while the buglers of the K.E.S. Cadet Corps blew Last Post.’ The base of the memorial remains, but the intervening years have not treated the memorial kindly.

The Stratford-upon-Avon Boat Club junior rowing crew, 1905. Alfred ‘Doc’ Smith is standing on the right.

ALFRED BENNETT SMITH – ‘Doc’ Smith, for he was never known by any other name – attended King Edward VI School between 1887 and 1893. He thrived, and clearly retaining an affection for his time there took an active part in the establishment of the Old Stratfordians Club, becoming the Honorary Treasurer in 1912. He lived in Chapel Street and became a ‘man of many parts’ and a familiar figure in Midland sporting circles. ‘Beneath a somewhat rugged demeanour were traits which commanded respect, and proclaimed him a large-hearted Englishman. He was generous, straightforward in all his dealings, thorough in everything he undertook and ever ready to assist others rather than to seek distinction for himself.’ It seems to have been the quality of self-abnegation, coupled with his unfailing fund of good humour, which won him so many friends.

He became a great lover of rugby and was a very popular player and captain of the Stratford club. ‘An extremely useful forward, never sparing himself, he frequently bore evidence of being in the thick of it.’ It was during his captaincy in the 1907-1908 season that the club realised its great ambition in winning the Midland Counties Cup by defeating Nuneaton, with ‘Doc’ Smith scoring one of the two winning tries. ‘With head thrown back and teeth set, he raced over for a try in that memorable match.’ In The History of Stratford-upon-Avon Rugby Club, it was recalled that ‘many were the sacrifices he made for the game, and when business claims prevented his appearance in the team as often as he desired, he gave attention to the valuable work of coaching the younger members. Those of us who are privileged to carry on will tell the boys with pride how ‘Doc’ Smith and his gallant comrades played for Stratford – and how they died for England.’

‘Doc’ Smith in the Stratford-upon-Avon XV, 1909

In the spring of 1908, the Army Council sanctioned the creation of a battery of horse artillery for the county of Warwick, the terms of service to be similar to those laid down for the Yeomanry. 1/1st Warwickshire Royal Horse Artillery was enthusiastically raised by Lord Brooke, the Earl of Warwick, at Warwick Castle, with headquarters at Clarendon Road in Leamington Spa and with a section in Coventry. One of the first recruits was ‘Doc’ Smith and by the outbreak of war he had risen to the rank of Quartermaster Sergeant.

He left on August 5 for a short period of training with the Warwickshire Royal Horse Artillery at Newbury in Berkshire, and in October they became the first territorial artillery to cross to France. Declining a commission and with his service in the reserve expired, Smith re-signed for the duration of the war. He clearly brought to his duties the same determination and dedication that were reflected in his approach to sport, and his Commanding Officer of the Warwickshire Royal Horse Artillery, Lieutenant-Colonel W.A. Murray D.S.O, wrote of his friendship with ‘Doc’ Smith: ‘I cherish the deepest feelings of gratitude to him for the way he helped me, and no one knows better than I how much he did for the welfare of every man in the battery. I shall always keep the fondest memories of our pleasant days in camp, when he was the life and soul of all that went on. He was always cheery, and a tower of strength. He was a tremendous help in showing the younger men how to bear discomforts and bad times with a light heart and smiling face. I never knew him put out or worried under the hardest circumstances. He treated danger with the same jocular cynicism that he treated discomfort, and I don’t think he paid any more attention to a shell than to a snowball.’

And it was a shell that killed him. Based near Ypres in 1917 during the height of the battle now called Passchendaele, the rain was torrential and sapped the humour of the most stoic. Writing to a friend in Stratford only six days before his death: ‘The weather here is wretched again which, of course, drags, but the terrible business I suppose will finish one day. I often wonder whether we shall ever see any sign of those old Rugger days and Regatta times once again. The prospect seems to get less and less. I had a look at the old canal this morning. When I last saw it it looked like a perfect regatta course. Now! Imagine one old canal on the mill pond with the banks broken down and the water all, or nearly all, run out. Each army has burrowed into either bank and on a wet day the scene of desolation is indescribable. They say that further forward is far worse. God help us when we advance then.’ On the evening of August 12 he was in charge of the pack horses taking ammunition to the gunners when the Germans put up a barrage on the road. One of the shells burst close to ‘Doc’ Smith killing his horse instantly and wounding him in the chest and side. A dressing station was close by, and his wounds were quickly dressed.

A friend visited and found Smith ‘quite cheerful though in considerable pain. Operated on in the morning he was very pleased with the way he was looked after in the hospital and I am sure that everything possible was done for him.’

However, he was not surprised when he visited the hospital the next morning to learn that ‘Doc’ had died at dawn. He was aged 39. In a letter to Smith’s parents and to his wife – ‘Doc’ married Lilian Mary Hine in April 1916 – he wrote that ‘the whole battery sympathises with you and your family in your great loss. We feel his loss too, so much had we taken ‘Doc’ into our hearts the last three years. His kindness and never-failing good humour had made many a bad time bearable not only in the battery but throughout the whole brigade. There are many who mourn for him not only as a brave man but as a personal friend.’

Buried close to the Casualty Clearing Station near Poperinge, his friends, including the sergeants of the whole brigade and many of the men, marked his grave with a wooden cross. At the end of the war, the site of three Casualty Clearing Stations became the Dozinghem Military Cemetery at Westvleteren, Poperinge. Michael Scott in his book on the cemeteries of the Ypres Salient wrote that many of the Casualty Clearing Stations were named by the soldiers ‘Bandaghem, Mendinghem and Dozinghem, which played ironically upon the Flemish language and spelling for their apt function.’

Dozinghem Military Cemetery, Krombeke

‘Doc’ Smith is also commemorated on the Stratford-upon-Avon War Memorial, the Memorial Screen and Reredos in Holy Trinity Church, the KES Boat Club Memorial in the Garden of Remembrance, on the Stratford-upon-Avon Cemetery War Memorial, and in the Memorial Library at King Edward VI School.